By Marty Neumier

- UBS – Unique Buying State of customers

- The faster globalism removes barriers, the faster people erect new ones. (40)

- Depending on your Unique Buying State, you can join any number of tribes on any number of days and feel part of something bigger than yourself. (41)

- Brands are the little gods of modern life, each ruling a different need, activity, mood, or situation. Yet you’re in control. If your latest god falls from Olympus, you can switch to another one. (41)

- It’s often better to be number one in a small category than to be number three in a large one. At number three your strategy may have to include a low price, whereas at number one you can charge a premium. (44)

- Can’t be number one or number two? Redefine your category. (45)

- Survival of the fittest – Volvo built a bulletproof brand when it turned a heavy, boxy vehicle into the “safe” alternative, a market niche they were able to own and defend for many years. Was that good enough for Volvo? Apparently not, because they’ve recently added fast, sexy vehicles to their lineup. (45)

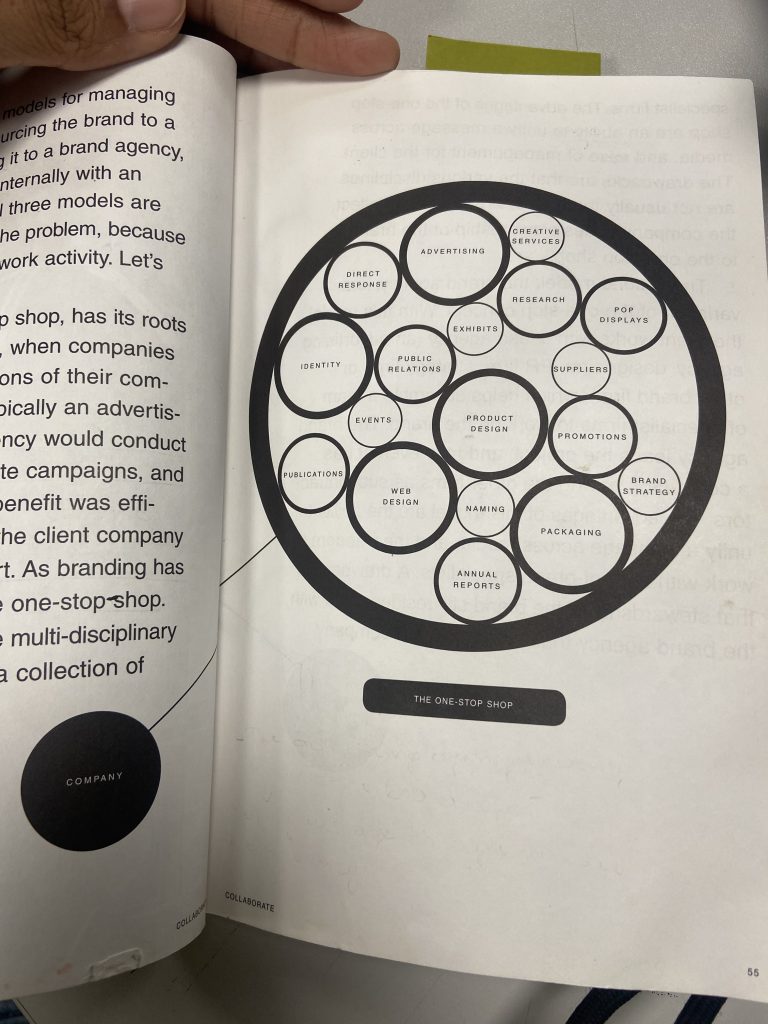

- The first model, the one-stop shop, has its roots in early 20th-century branding, when companies routinely consigned large portions of their communications to a single firm, typically an advertising agency. The advertising agency would conduct research, develop strategy, create campaigns, and measure the results. The main benefit was efficiency, since one person within the client company could direct the entire brand effort. As branding has grown more complex, so has the one-stop shop. Today’s one-stop shop is either a single multi-disciplinary firm, or a holding company with a collection of specialist firms. The advantages of the one-stop shop are an ability to unify a message across media, and ease of management for the client. The drawbacks are that various disciplines are not usually the best of breed, and, in effect the company cedes stewardship of the brand to the one-stop shop. (55, 56)

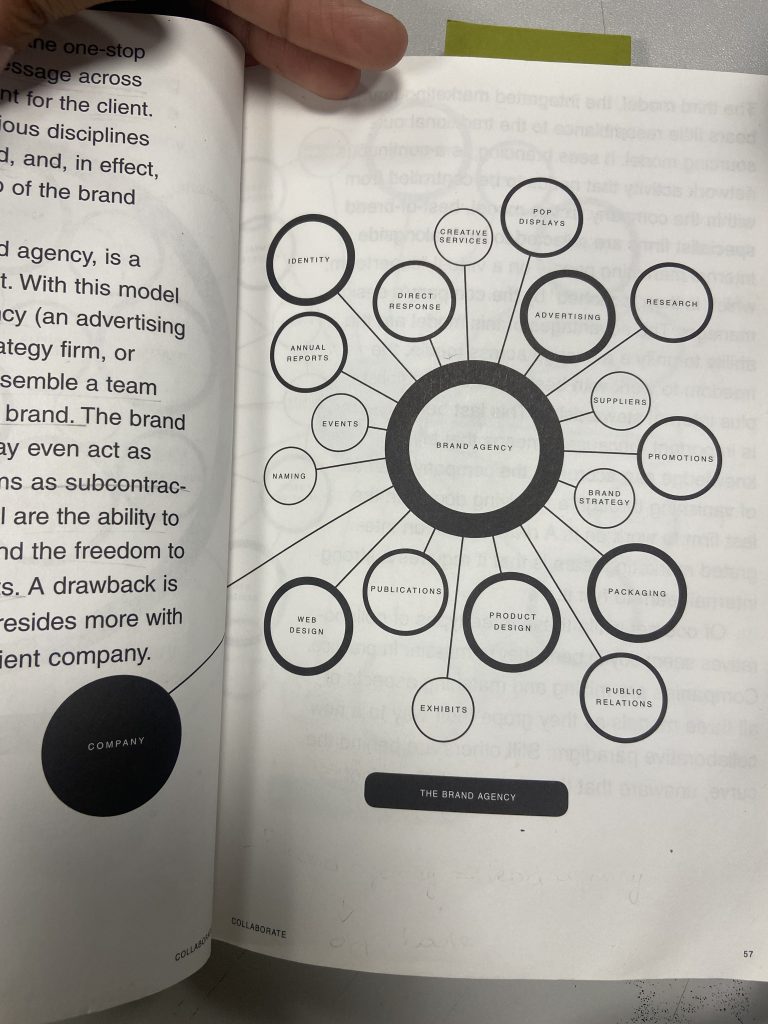

- The second model, the brand agency, is a variation of the one-stop concept. With this model the client works with a lead agency (an advertising agency, design firm, strategy firm, or other brand firm), which helps assemble a team of specialist firms to work on a brand. The brand agency leads the project, and may even act as a contractor, paying the other firms as subcontractors. The advantages of this model are the ability to unify a message across media, and the freedom to work with the best-of-breed specialists. A drawback is that stewardship of the brand still resides more with the brand agency than with the client company. (56)

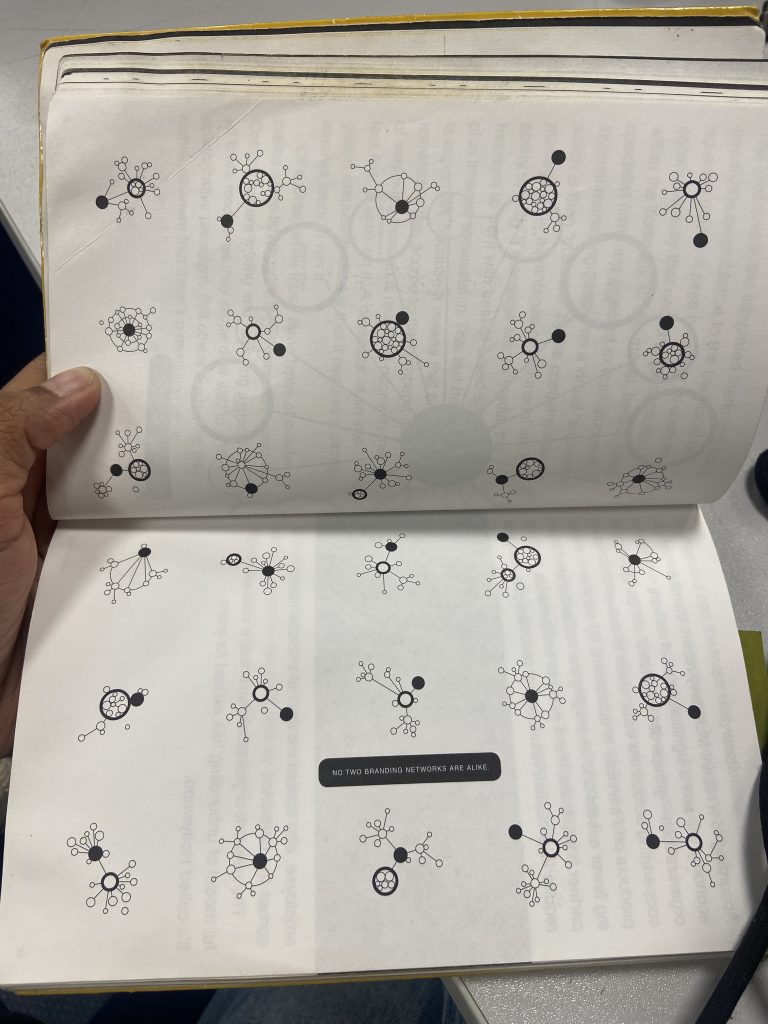

- The third model, the integrated marketing team, bears resemblance to the traditional out-sourcing model. It sees branding as a continuous network activity that needs to be controlled from within the company. In this model, the best-of-breed specialist firms are selected to work alongside internal marketing people on a virtual “superteam”, which is then “coached” by the company’s design manager. (58)

(insert picture of The Integrated Marketing Team model)

(insert picture of no two branding networks being alike)

- A combination of good strategy and poor execution is like a Ferrari with flat tires. Execution – read creativity – is the most difficult part of the branding mix to control. It’s magic, not logic, that ignites passion in customers. (73)

- To achieve originality, we need to abandon the comforts of habit, reason, and the approval of our peers, and strike out in new directions. (76)

(insert creative and logical thinking image)

- MAYA – Most Advanced Yet Acceptable Solution, by industrial designer Raymond Loewy. Creative professionals excel at MAYA. While market researchers describe how the world is, creative people describe how it could be. Their thinning is often so fresh that they zag even when they should zig. An effective us of the MAYA principle was the career of The Beatles. They began in the early 1960s with songs that were commonly acceptable, then raised the bar of innovation one record at a time. By the end of the decade, they had taken their audience on a wild ride from the commonplace to the sublime, and in the process created the anthems for a cultural revolution. Their formula, one critic observed: “They never did the same thing once.”. (77)

- Here’s an example of a typical reading sequence: 1) the shopper notices the package on the shelf – the result of good colours, strong contrast, an arresting photo, bold typography, or other technique; 2) the shopper mentally asks “What is it?”, bringing the product name and category into play; 3) then “Why should I care?”, which is best answered with a very brief why-to-buy message; 4) which in turn elicits a desire for more information to define and support the why-to-buy message; 5) the shopper is finally ready for the “mumbo-jumbo” necessary to make a decision – features, price, compatibilities, guarantees, awards, or whatever the category dictates. (94)

- Advertiser David Ogilvy often claimed that by changing one single word in a headline one could increase effectiveness of an advertisement by up to ten times. (94)

- I’ve proven (at least to myself) that by getting the reading sequence right, and by connecting product features to customer emotions, a package can increase product sales by up to three times, sometimes more. (95)

- What are the invisible chains keeping web design from achieving its full potential? It boil down to three: technophobia, turfismo, and featuritis. (98)

- Technophobia – the fear of technology, keeps a lot of skilled designers out of web design. The result is that web design, thus deprived of disciplined designers, still falls below the aesthetic level considered standard for catalogues, annual reports, and books. (98)

- Turfismo, the second problem, is the behind-the-scenes politicking that transforms the home page into a patchwork of tiny fiefdoms. You can see exactly which departments have the power and which don’t, as turfy managers fight for space on the company marquee. Simplify the home page? Sure, but not at my expense! (98)

- Featuritis, an infectious disease for more, afflicts everyone from the CEO to the programmer. The tendency to add features, articles, graphics, animations, links, buttons, bells, and whistles comes naturally to most people. The ability to subtract features is a rare gift of the true communicator. An oft-heard excuse for cluttered pages is that most people hate clicking, and prefer to see all their choices on one page. The truth is, most people like clicking – they just hate waiting. (99)

- All brand innovation, whether for a website, a package, a product, an event, or an ad campaign, should be aimed at creating a positive experience for the user. The trick is in knowing which experience will be the most positive – even before you commit to it. (99)

( Insert chart on page 104)

- The chart divides the world into four mindsets, based on people’s job interests: applying, creating, preserving, and discovering. “Appliers”, for example, gravitate toward graphics that are precise, realistic, and familiar, while “creators” go for the lyrical, abstract, and novel. Guess what? If you divide the chart down to the middle, you have an approximate map of the left and the right brain. (109)

- Focus groups are particularly susceptible to something called the Hawthorne Effect – the tendency for people to act differently when they know someone’s watching. In groups, it seems, people just want to show off. Focus groups are a good starting point for quantitative research. One-on-one interviews can give you enough insight to choose with confidence. If you’re looking for an understanding of audience behaviour, ethnographic observation can turn up some suggestive insights. (110)

- The Swap Test: Wanna check out the effectiveness of your brand icon? Here’s a simple test you can perform without leaving your office. Swap part of your icon – the name of the visual element – with that of a competing brand, or even a brand from another category. If the resulting icon is better, or no worse than it was, your existing icon has room for improvement. By the same token, no other company should be able to improve it’s icon by using part of yours. (114)

- The Hand Test: Lets you check the effectiveness of ads, brochures, web pages, and other brand communications. Take any piece of visual communication and cover up your trademark with your hand. Can you tell whose piece it is? Even without a trademark, those familiar with your brand should be able to tell who’s talking just by its “voice”, or the look and feel of the materials. (115)

- Concept test: Create a range of prototypes of the brand element in question. Get them down to two or three. Next, present the prototypes to at least 10 members of the real audience. .Then ask them such series of questions: which of these promises is the most valuable to you? Which company would you expect to make a promise like this? If company X made this promise, would that make sense? What other type of promise would you expect from company X? Always follow up with why, because the answer of why will contain the seed to the next question. (119)

- A brand is what they say it is, not what you say it is. (125)

- All brand expressions, from icons to actual products, need to score high in five areas of communication: distinctiveness, relevance, memorability, extendability, and depth.

- Distinctiveness is the quality that causes a brand expression to stand out from competing messages. It often requires boldness, innovation, surprise, clarity, not to mention courage on the part of the company. Is it clear enough and unique enough to pass the sway test?

- Relevance asks whether a brand expression is appropriate for its goals. Does it pass the hand test? Does it grow naturally from the DNA of the brand? These are good questions, because it’s possible to be attention-grabbing without being relevant, like a girly calendar issued by an auto parts company.

- Memorability is the quality that allows people to recall the brand or brand expression when they need to. Testing for memorability is difficult, because memory proves itself over time. But testing can often reveal the presence of its drivers such as emotion, surprise, distinctiveness, and relevance.

- Extendability measures how well a given brand expression will work across media, across cultural boundaries, and across message types. In other words, does it have legs? Can it be extended into a series if necessary? It’s surprisingly easy to create a one-off, single-use piece of communication that paints you into a corner.

- Depth is the ability to communicate with audiences on a number of levels. People, even those in the same brand tribe, connect to ideas in different ways. Some are drawn to information, others to style, and still others to emotion. There are many levels of depth, and skilled communicators are able to create connections at most of them. (126-127)

- As entrepreneurial consultant Guy Kawasaki advises his clients: “Don’t worry, be crappy” Let the brand live, breathe, make mistakes, be human. Instead of trying to present a Teflon-smooth surface, project a three-dimensional personality, inconsistencies and all. Brands can afford to be inconsistent – as long as they don;t abandon their defining attributes. They’re like people. (133)

- The old paradigm in which identity systems try to control the “look” of an organisation only results in cardboard characters, not three-dimensional protagonists. The new paradigm calls for heroes with flaws – living brands. (135)

- The growing need for internal stewardship has given rise to the appointment of what we might call chief brand officers – CBOs – highly experienced professionals who manage brand collaboration at the highest corporate level. CBOs are rare birds, because they need the ability to strategize with the chief, and also inspire creativity among the troops. In effect they must form a human bridge across the brand gap, connecting the company’s left brain with its right brain, bringing business strategy in line with customer experience.

- A brand is not a logo. A brand is not a corporate identity system. It’s a person’s gut feeling about a product, service, or company. Because it depends on others for its existence, it must become a guarantee of trustworthy behaviour. (146)

- Quick summary: (from 149)

- A brand is a person’s gut feeling about a product, service, or company. It’s not what you say it is, it’s what they say it is.

- Branding is the process of connecting good strategy with good creativity. It’s not the process of connecting good strategy with poort creativity, poort strategy with good creativity, or poor strategy with poort creativity.

- The foundation of a brand is trust. Customers trust your brand when their experiences consistently meet or beat their expectations.

- Modern society is information rich and time poor. The value of your brand grows in direct proportion to how quickly and easily customers can say yes to your offering.

- People base their buying decisions more on symbolic cues than features, benefits, and price. Make sure your symbols are compelling.

- Only one competitor can be the cheapest – the others have to use branding. The stronger the brand, the greater the profit margin.

- The charismatic brand is any product, service, or company for which people believe there’s no substitute. Any brand can be charismatic, even yours.

- To begin building your brand, ask yourself three questions: 1. Who are you? 2. What do you do? 3) Why does it matter?

- Our brains filter out irrelevant information, letting in only what’s different and useful. Tell me again, why does your product matter?

- Differentiation has evolved from a focus on “what it is” to “what it does” to “how you’ll feel” to “who you are”. While features, benefits, and price are still important to people, experiences and personal identity are even more important.

- As globalism removes barriers, people erect new ones. They create tribes – intimate worlds they can understand and participate in. Brand names are tribal gods, each ruling a different space within the tribe.